Introduction to Parallel Computing

At the end of this class, you should be able to:

- Explain the potential benefits of using parallel computing

- Use the correct terminology when discussing parallel computing

- Select the appropriate type of parallel architecture for a computational task

- Understand the various types of parallel communication

Working in parallel

Parallel computing can help us reduce the wallclock time of a computational task by distributing the workload among a number of processors. Take the VERY simple task of copying a 1,000-page book: if a single person on average requires 1 hour to copy 1 page, it will take about 125 working days for that single person to copy the entire book. If we now split the workload among 50 people, we will have the work done in about 2.5 working days. In HPC terminology, using 50 processes (or CPUs) we ran the program (copying the book) 50 times faster. We can therefore say that, ideally, we would like a program to run

- Not all parts of the program can be parallelized.

- Parallelization may lead to additional sources of overhead, such as communication between processes.

An efficient parallelization aims at achieving the following results:

- Limit interprocessor communication: the time processes spend on communicating with each other is not time spent computing.

- Balance the load between processes: in such a way that all processors are equally busy (generally we don’t want one processor doing all the work while others wait idling).

Ideally, from a performance perspective, we would like ZERO (or very little) communication between processors. In parallel computing, we distinguish between (i) an embarrassingly parallel problem which requires little (or NO) interaction between processors (e.g. copying the 1000-page book), and (ii) a tightly coupled problem in which a lot of interaction/communication is required between the parallel tasks. One of the most challenging, yet very important questions in parallel computing is: how do we divide the work among the processors? In other words, how do we parallelize our code?. The parallelization strategy heavily depends on the memory structure of the system used. Therefore, before diving into several ways of splitting up the workload, we should focus on …

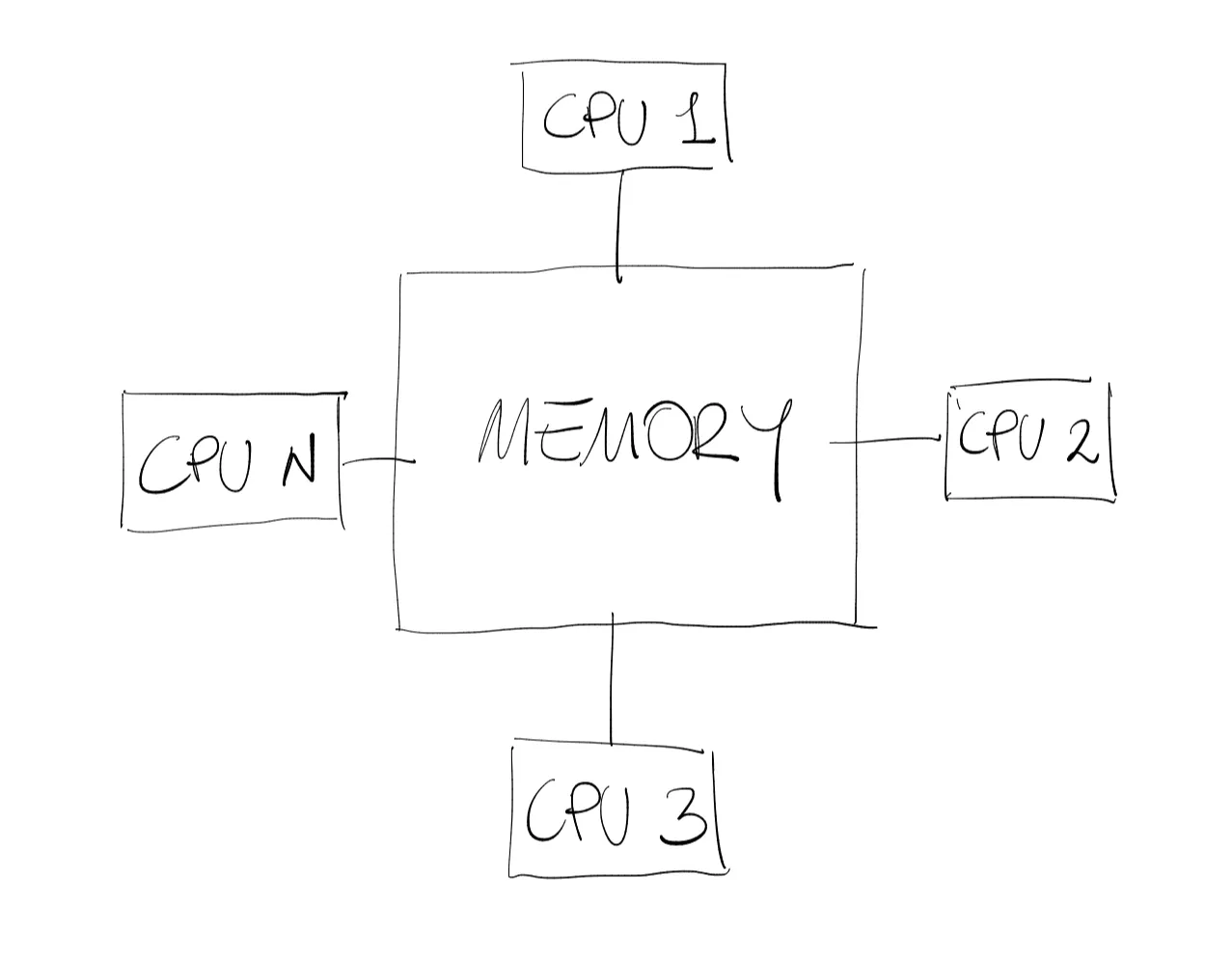

Shared memory architecture & shared parallelism

When a system has a central memory and each CPU can access the same memory space it is known as a shared memory platform. A single node in a computer cluster might look something like this:

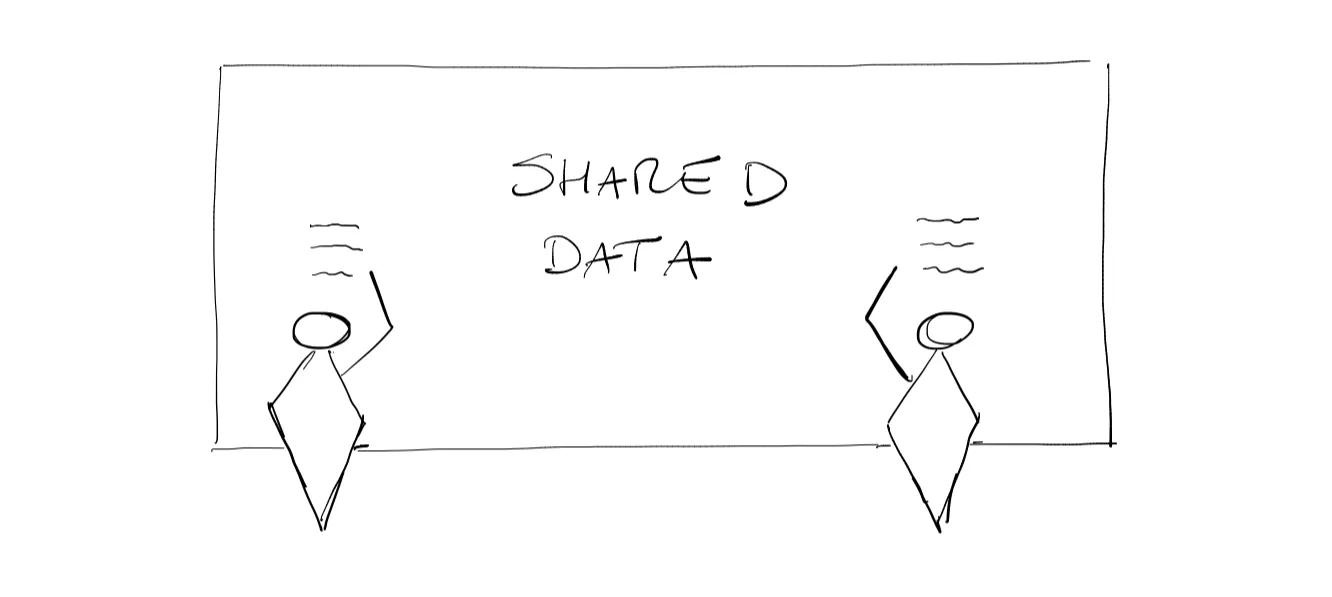

In a shared memory architecture, CPUs can operate independently on different tasks, however they see the same data in the same memory space. In a real-life easy example, it is like having 2 students working independently on two problems using a common very large blackboard containing important data for both (see figure below).

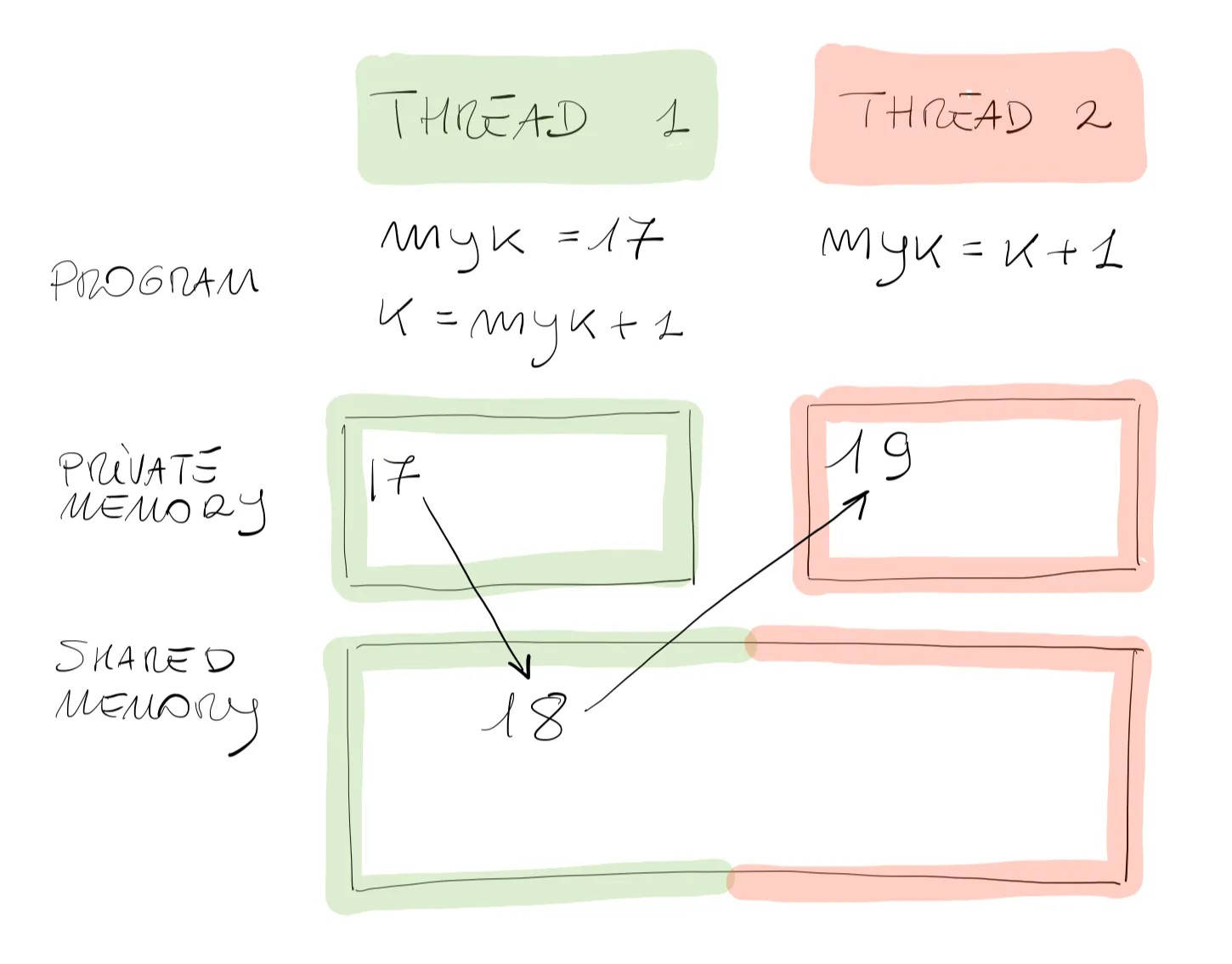

The great advantage of this structure is that when the CPU (students) needs some data, it can directly access the shared memory to fetch it (common blackboard), and this process is usually very fast. However, it is very easy to see that problems might arise if student 1, for instance, changes something on the board (shared memory). The change may affect the workflow of the second student. This situation is commonly known as a race condition, which occurs when 2 or more CPUs (or threads) try to modify some data in the shared memory at the same time. This problem is due to the fact that the thread scheduling algorithm does not know a priori which thread is going to try to access the data first (or when the students will need access to the board). It is in the hands of the developer to avoid such a condition. We will not go into details, but one way of mitigating this problem is to equip each thread with its own small private memory. In the previous simple example, it would be as if each student had their own notebook. So, what does a parallel algorithm look like in a shared memory architecture? Here is a very simple example:

Thread 1 is not able to see the

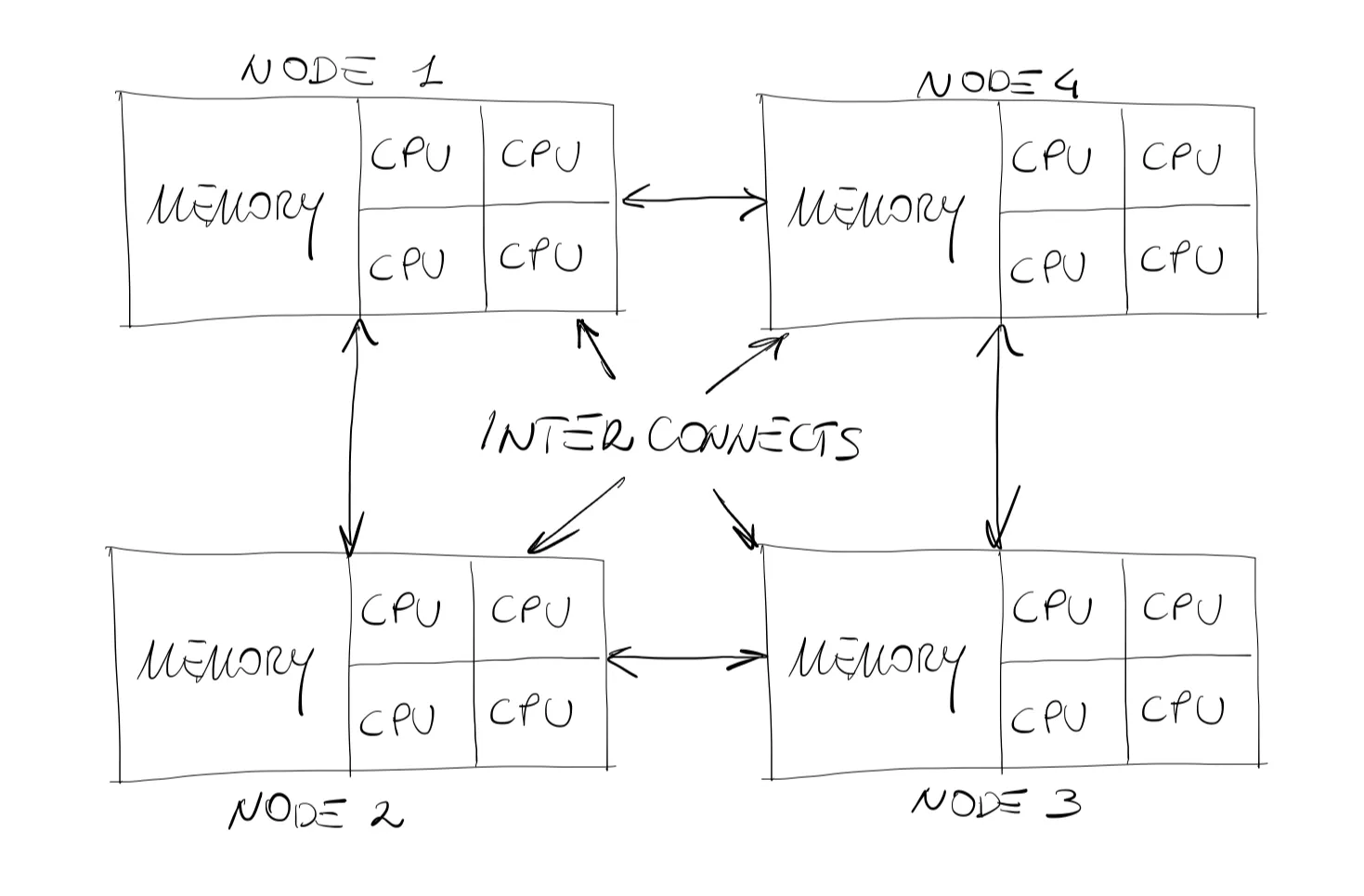

Distributed memory architecture & distributed parallelism

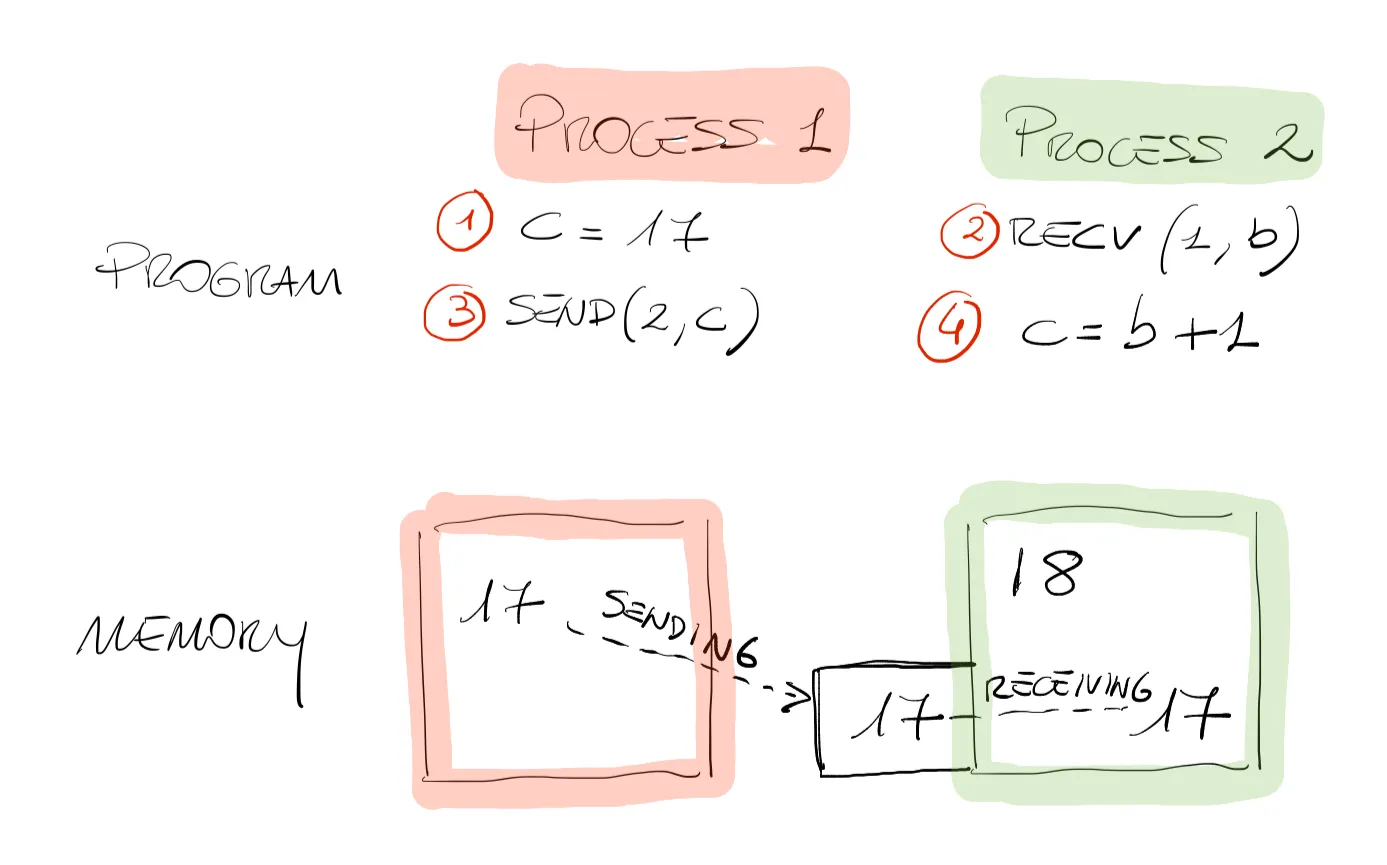

Multi-threading is not suited, on the other hand, for distributed memory systems. As shown in the figure above, in a distributed memory architecture, each processor (or node) has its own local memory, and they communicate with each other through message passing. This means that they can only access their own memory locations, and exchange information with other processors (or nodes) through sending and receiving messages.

With a very simple example shown in the figure above, it is like having 2 students sitting in separate rooms each with a blackboard working at the same problem. Student 1 cannot see the data on the board of student 2 and vice versa, however they may depend on each other for the solution to the problem. They are equipped with a telephone, and the only solution they have to advance towards the solution is calling each other and passing messages. The key point of this approach is that as soon as student 1 (process 1) asks the value of

Process 1 assigns a value to

Comparing this approach with the shared-based structure we saw before, we can say that in message-passing, the synchronization is automatic (e.g. the student waits until the phone rings), however the parallelization is much more complicated from a developer point of view. It requires more thinking and might be a bit cumbersome at the beginning. However, there are two great advantages of distributed memory parallelism:

- There is no risk whatsoever to corrupt someone else’s data.

- In a distributed memory parallelism, we have the ability to scale up the total memory of the problem, whereas the shared memory parallelism is limited to the available physical memory shared by the processes.

Interprocessor communication: message passing

In message passing, the communication can be synchronous or asynchronous.

- A synchronous send works just like faxing a letter. You fax the letter and wait for a message from the other end that tells you that the letter has been received. This process wastes a bit of computational resources, as the sending process hangs for a confirmation instead of doing useful work.

- An asynchronous send work just like mailing a letter. You put your mail in the mailbox and the postman will take care of the delivery process. The sending process does not know when the letter will be received but it can continue to do useful work.

In HPC terminology, send or receive calls involving only one sender and one receiver are known as point-to-point communication. However, just like fax or mail, one could send the same message to several other processes (not just one) therefore initiating what is known as collective communication. As we shall see in the following section that this is a very common scenario in parallel computing. Collective communication can take the form of a broadcast, where the same data is shared with all processes, or (more commonly) of a scatter send where only one processor holds all the data it separates and scatters towards all the other processes. For collective type communication we also often use the gather call where all processes, after they are done with their calculations, send all the data back to one processor. The framework that provides this parallelism strategy is the Message Passing Interface (MPI).

It is important to note that MPI is not a programming language but rather a library of functions that programmers (or code developers) call from within a C, C++, Fortran, Python code to write parallel programs. Later on in this section we will use the MPI library of Python also known as mpi4py. This library provides Python bindings for the Message Passing Interface standard, allowing Python applications to exploit multiple processors on workstations, clusters and supercomputers. For more in depth information on parallel computing we refer the interested students to Compute Ontario dedicated training courses on the subject.

Domain decomposition

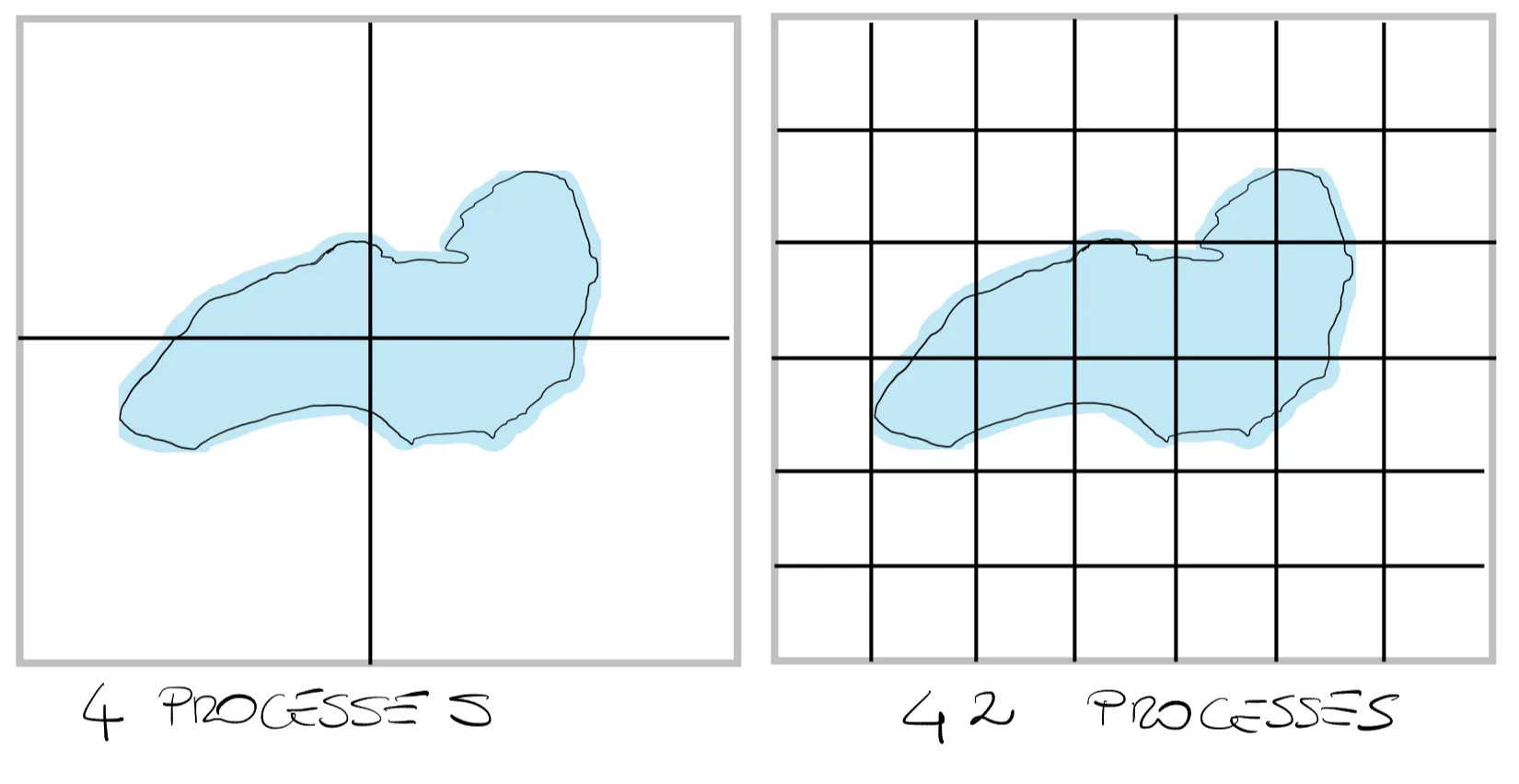

The most common parallelization strategy, especially in computational fluid dynamics, is known as domain decomposition, in which we split up the computational domain into smaller sub-problems that can be completed by each processor. As easy as it might sound, splitting the domain up in sub-problems is no easy task, and it is associated with a cost mostly due to the overhead of communication between processes. With the very important goal in mind of minimizing communication to maximize computation, let us consider a first simple example: say that we are using a weather forecasting algorithm to study weather changes above lake Ontario.

The figure above shows two very different scenarios: on one side we decomposed the domain in 4 sub-domains each of which is assigned to process or CPU. On the other side we have split, the domain up into 42 processes (or CPUs). The key point of this simple example is that although case 1 limits communications between processes (given that there are only 4) it probably does not take advantage of the computational power available. In case 2 on the other hand, although we managed to split the problem up into several sub-problems, we might run into a larger communication overhead. Therefore, in HPC terminology, the first aspect to consider when trying to decompose a domain is the granularity of the problem. In parallel computing, the term granularity refers to the communication overhead between multiple processors, and it is defined as the ratio of computation time (time required to perform the computation) to communication time (time required to exchange data between processors):

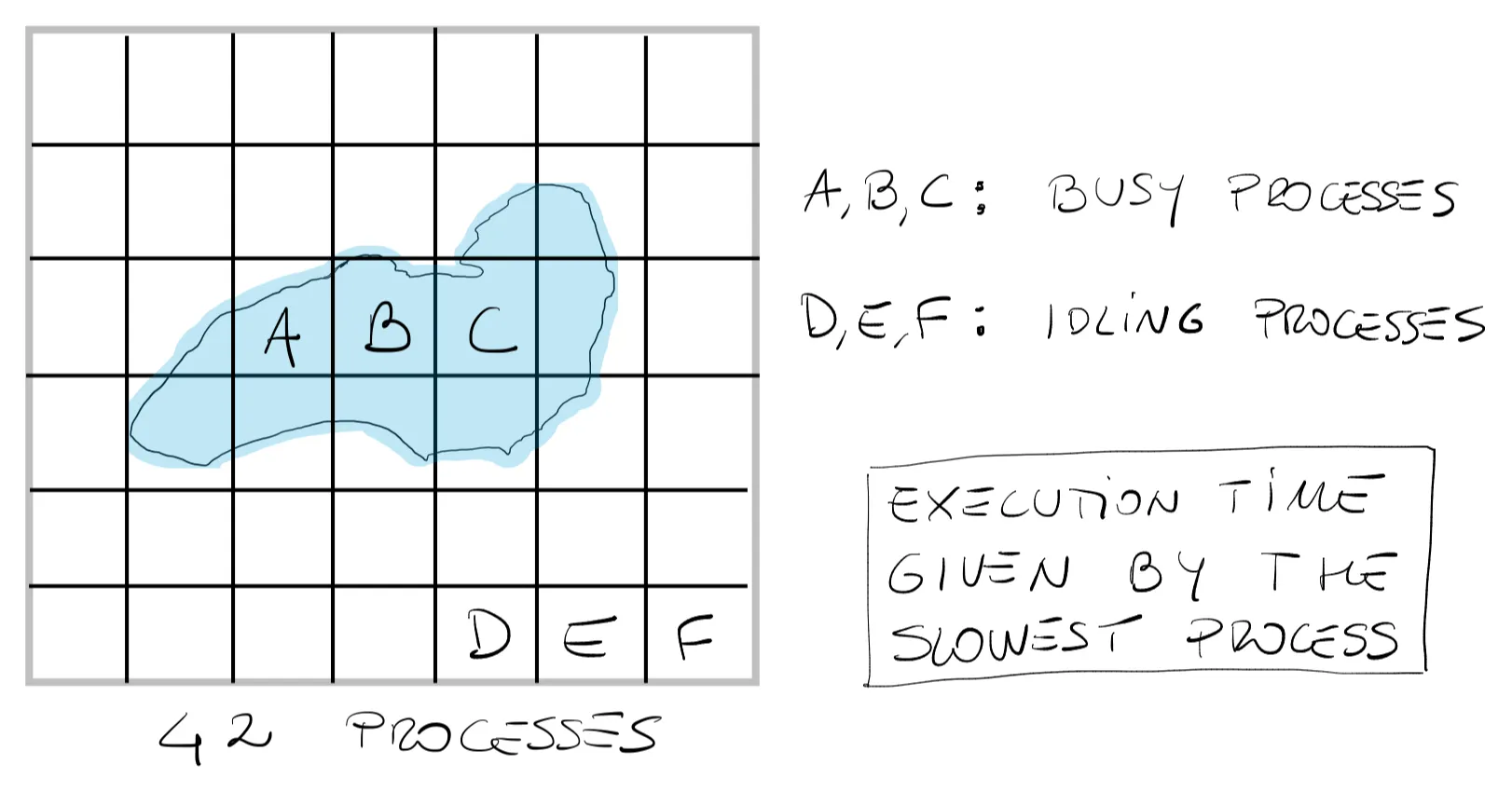

Another very important aspect to consider is the load balance. Following the previous example, say that we now have a software that allows us to measure water properties. If we run this process using the decomposition of 42 processes, we will probably run into a load imbalance problem. As you can see from the figure below, processes D,E,F will finish their assigned task quite quickly (as they have no water in their sub-domain) while processes A,B,C will be busy doing computation. This is also true for many other processors in this example. The result is that, out of all the processors we are using, only a small fraction are doing useful work while a great percentage of them sit waiting (idling). This is a very undesirable scenario in parallel computing as the execution time of a parallel task is always determined by the slowest processor.

As a general rule, each processor should have roughly the same amount of work (a load balance among processors).

Farming jobs

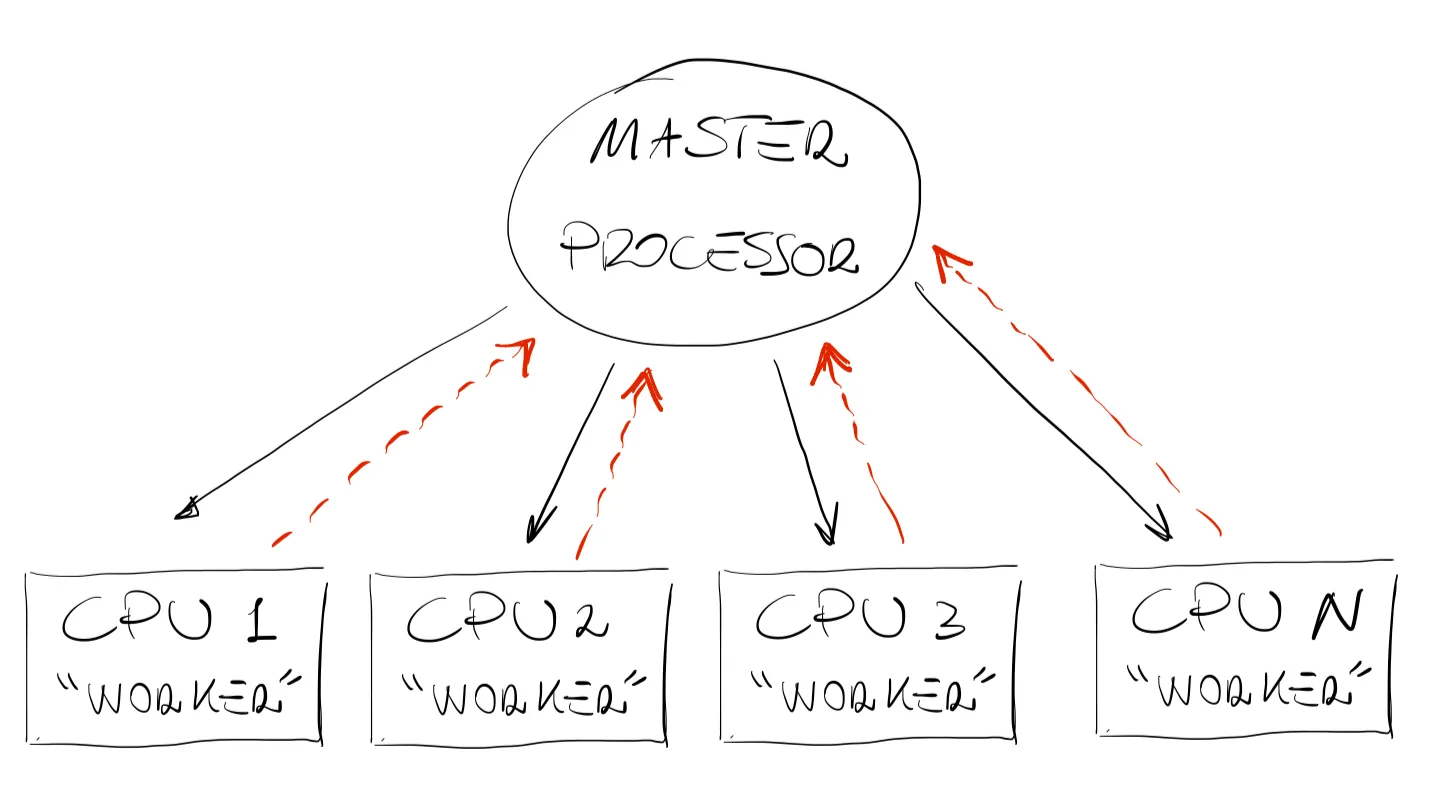

A very common solution to a load imbalance issue is to implement **master worker parallelism ** commonly knows as task farm (see figure below).

In this configuration, after the domain has been decomposed, processors are subdivided into one master and

The great advantages of this structure are the following:

- Communication is limited between master and worker.

- Load imbalance is prevented. Often the number of tasks is much larger than the number of processors, and in this scenario as soon as a worker has completed its task the master can assign a new task.

- Resilience. In this type of scenario if something happens to a CPU, or to a node, or if a process is stuck, the final solution is not impacted as the master processor can redistribute the workload of the affected CPU to other workers.

However, it is easy to see that this type of parallelization only works well when we have distinct, independent tasks or, in other words, when limited communication is required between processes. Another very common strategy is:

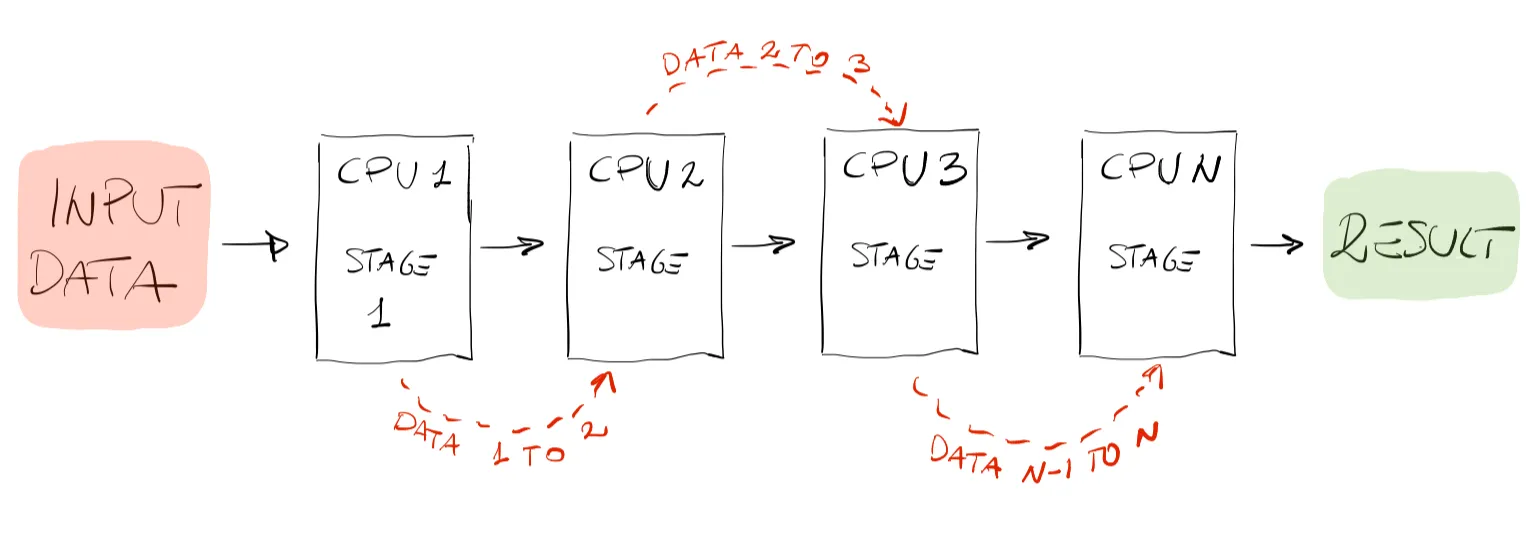

Pipelines

As shown in the figure above, another common parallel architecture used for computation is the pipeline parallelism. Suppose your program is composed of well-defined separate stages, one could divide those stages among each processor. Think of the assembly line of a new PC. Stage 1 could be putting together the motherboard, stage 2 could be attaching the display adapter, stage 3 could be attaching the solid state memory, and so on. One great advantage of this architecture, as can be easily seen in the figure, is that there is a 1D flow of data. In other words, stage

This is a very efficient way of parallelizing tasks and most importantly limits the amount of communication required. One might notice, however, that this parallelism is not well suited for scaling. For instance, what if the problem we are trying to solve has only 3 stages? Are we limited to using only 3 processes? Or what if something goes wrong in the pipeline and a process gets stuck? These are all valid questions, which highlight potential shortcomings of this type of parallel architecture.

MPI in Python

In this example, we will use the message passing interface (MPI) in Python to show what has been discussed earlier. Similar libraries can be found in any other programming language (Julia, Fortran, C++, etc). The general send and receive types of communication follow a few steps:

- Process 1 decides a message needs to be sent to process 2.

- Process 1 then prepares all of the necessary data into a buffer for process 2.

- Process 1 indicates that the data is ready to be sent to process 2 by calling the send function.

- Process 2 first acknowledges that it wants to receive data from process 1 and then asks for the data by calling the recv function.

What is clear from the above workflow is that calls to send/recv are always paired, and every time there is a process sending a message, there must be a process that also indicates it is ready to receive the message. Failing to do so might result in deadlocks in your code. Deadlocks occur when a process is waiting to receive a message that is never sent.

At this point, one might ask but how does a process know where to send the message?

In general, the number of processes used in a given program is fixed and defined at the beginning of execution. Each of the processes is assigned a unique integer identifier starting from 0. This integer is known as the rank of the processor. Here, we will use rank and process as synonyms. As their unique identifier, the rank is also the way a process is selected when sending/receiving messages. MPI processes are organized into logical collections that define which processes are allowed to send and receive messages. A collection of this type is known as a communicator.

There is one special communicator when an MPI program starts, which contains all the processes in the MPI program: the MPI.COMM_WORLD. In MPI4py, comm is the base class of communicators. One process can learn of other processes by using 2 fundamental methods given by the communicator:

- Comm.Get_size: returns the total number of processes contained in the communicator

- Comm.Get_rank: returns the rank of the calling process within the communicator (different for every process in the program).

Here is a very simple application of what we have learned so far. By running the script below using mpiexec -n p python hwmpi.py, every worker will print “Hello world”.

# Hello world in parallel

from mpi4py import MPI

comm = MPI.COMM_WORLDworker = comm.Get_rank()size = comm.Get_size()

print("Hello world from worker ", worker, " of ", size)[username@nia-302~]$ mpiexec -n 4 python hwmpi.pyHello world from worker 0 of 4Hello world from worker 1 of 4Hello world from worker 2 of 4Hello world from worker 3 of 4Example: a parallel sum

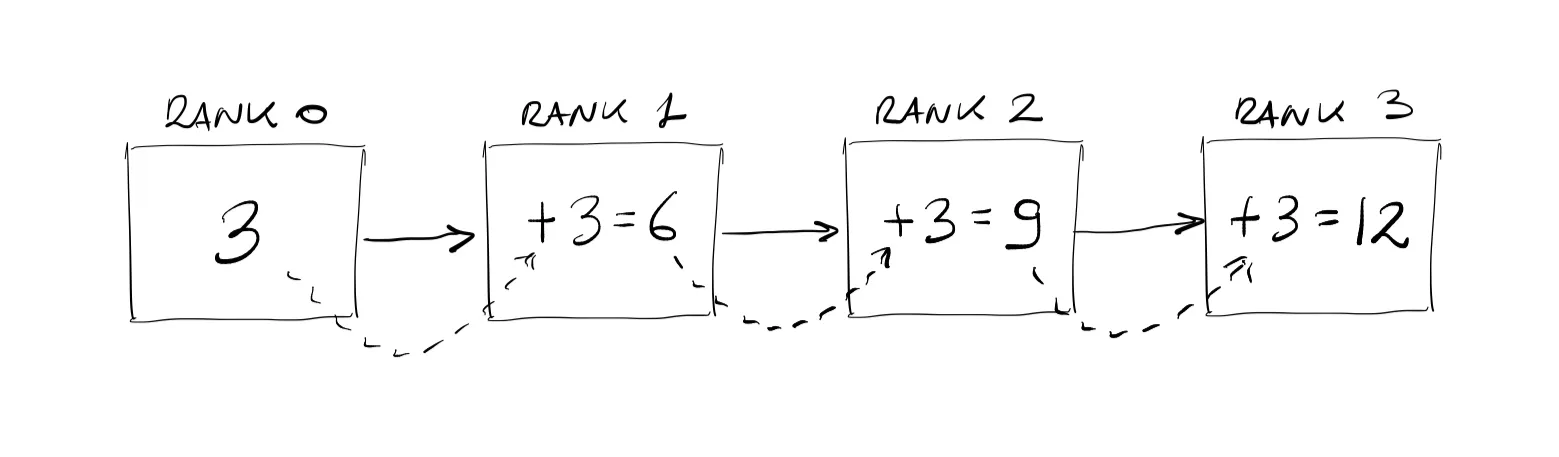

We now wish to write a parallel program to perform the following task:

# A parallel sum

from mpi4py import MPI

comm = MPI.COMM_WORLDworker = comm.Get_rank()size = comm.Get_size()

a=3

if(worker == 0): print(size," processes started!") comm.send(a, dest=worker+1) print(worker," I am sending: ",a)elif worker == size-1: rec = comm.recv(source=worker-1) print(worker," my step is ",rec+3)else: rec = comm.recv(source=worker-1) comm.send(rec+3,dest=worker+1)

print(worker," my step is ",rec+3)QUIZ

1.4.1 You are considering implementing a task farm parallelism using only 3 processors for a tightly coupled computational problem. Is this a good idea?

1.4.1 Solution

Probably not. Task farm parallelization is primarily suited for computational tasks that are independent calculations and where information does not need to be exchanged between workers. Furthermore, if we only use 3 processors, one of which is the master node, then the computational task is only completed by only 2 processors. Other parallelization strategies should be considered.

1.4.2 If you need to solve a computational task with a very large memory need, is it preferable to use a shared or distributed memory architecture?

1.4.2 Solution

It depends.

- The memory available in a shared memory architecture is limited by the available shared memory among all processors. Thus, if the computational problem requires more memory than the available shared memory, a distributed memory architecture is needed.

- If the memory is sufficient for a shared memory architecture, then we need to consider the details of the code, and particularly the information transfer between processors to determine which architecture is better suited.

Having finished this class, you should now be able to answer the following questions:

- What are the benefits of using parallel computing?

- What are the differences between a distributed- and shared-memory parallelization strategy?

- Explain the difference pipeline and task-farm parallelism.

- List all types of parallel communications.